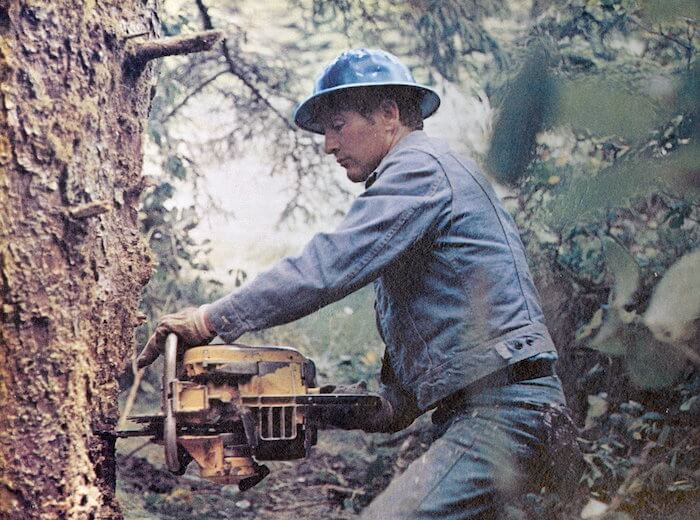

Fonda, Jaeckel, some crashing trees-and one deadly log-stand out, and show up what is otherwise splintered and unpolished. Even with locations at their feet, there’s little sense of place conveyed other than some shots of the Siletz River and segments in a hillside clear-cut, nothing calls Oregon to mind, and crucial ambient natural details-forest, coast, wildlife, weather (!!) are barely there. The camera work employs too much telephoto lens jazz. Tone, then, is absent in a number of ways. The 1933 standard “Good Night, Irene” would be the obvious pick, with its lyrics “ sometimes I take a great notion to jump in the river and drown“.

#Sometimes a great notion movie images movie

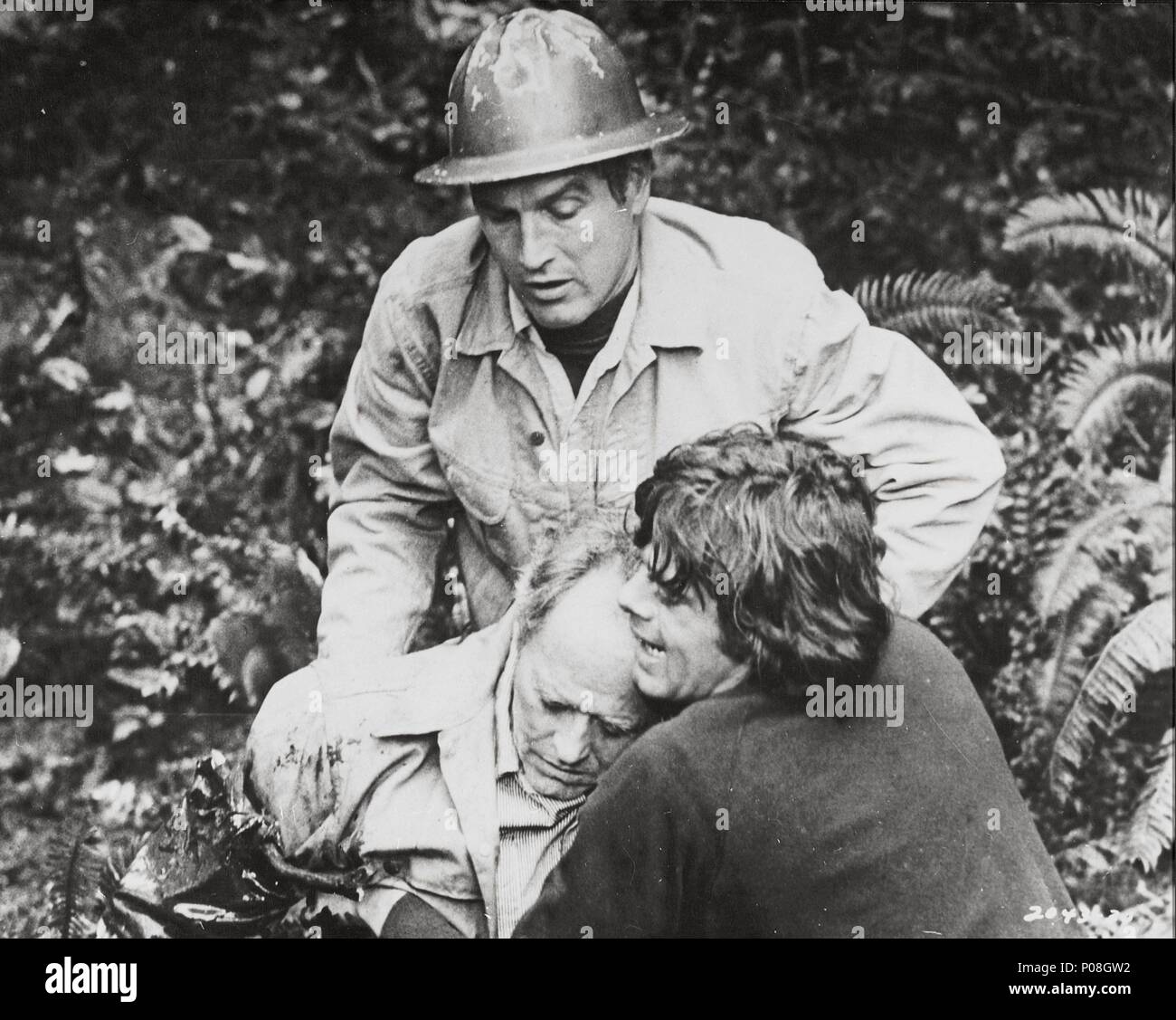

Scored by Henry Mancini, the music background, rather than the tavern honky tonk of Kesey’s book, appropriate to the milieu, is instead given ersatz country coating more fitting for a TV movie about moonshiners. Yet the syrupy number really belongs in another movie, just one of the misplaced ingredients to add to those missing in action from the script and in Newman’s functional but flat direction. The film’s other Academy Award bid went to the song “All His Children”, warbled (nicely enough) by Charley Pride over the credits. A dependable supporting hardy from way back (starting at age 16 in 1943’s Guadalcanal Diary), Jaeckel-44, fit enough to pass for 30-gets his career-high role, and one of the all-time most gripping exit scenes, moving enough to notch an Oscar nomination for Supporting Actor. Fonda, 65, plunges into “old man” territory with the same laid-back but steely sincerity that he always brought to the job at hand: he’s totally believable as an ornery roughneck, and his hospital-bed moments are beautifully done. Fonda, Jaeckel and a few sequences of arduous, inherently risky logging make the movie work. Remick’s character is under-developed, Sarrazin is too diffident to raise sufficient empathy. Newman’s charismatic as usual, though the role is basically another variation of his guy-with-a-chip (off a log this time). Two weeks into the shoot, director Richard Colla was fired, and Newman took over that chore, filming around the central Oregon coastal towns of Toledo and Newport. The novel was set in the mid 50s, the film moved that up 15 years to be current with the social zeitgeist of the early late 60s/early70s. Off the mark, a hurdle for John Gay’s script was taking Kesey’s 700 page forest of complex viewpoints and literary devices, grown out of the author’s intimacy with the subject, and pruning it to a marketable 113 minute running time without clear-cutting it into a patchwork of stumps. Scrappy on the surface, but choppy in the depth department, the movie is entertaining but flawed. Honey-sweet, that’s all there is…the whole ball of wax.” To work, and eat, and screw, and sleep, and drink, and keep on goin’.

Why? Because as old rooster Henry tells fed-up Viv “ Why, hell, doncha know? To keep on goin’, that’s what. Tempers fray, but there’s hotcakes to wolf down, beer to slug, and by-God-timber to fall. Wayward college-educated (therefore suspect, and he’s hippyish to boot) stepson ‘Lee’ (Michael Sarrazin) turns up, with mixed motivations for rejoining the family, tearing scabs off unhealed private wounds much as the Stampers public refusal to buckle and join union strikers chafes the local community.

#Sometimes a great notion movie images code

Bull-headed ‘Hank’ (Newman) continues the “ never give an inch” code set by lusty patriarch ‘Henry’ (Henry Fonda), aided by exuberant cousin ‘Joe Ben’ (Richard Jaeckel), while Hank’s wife ‘Viv’ (Lee Remick) is wearily resigned to the tribe’s testosterone touting. The ‘Stamper’ clan are independent loggers on the central Oregon coast. The notion might’ve been great, but the potion shorted on the flavoring. Considering the cast, the legendary, daunting source material-long considered “unfilmable”-and the waffling production spilling over its $3,660,000 budget, the box office returns of around $8,000,000 were disappointing, not buoyed by two Oscar nominations.

Highlighted by one unforgettable, universally praised scene, the overall effort otherwise drew polite applause rather than cheers, then Universal botched things with an unhelpful title change to Never Give An Inch.

SOMETIMES A GREAT NOTION had been a pet project of Paul Newman’s for seven years, having quickly secured rights to adapt Ken Kesey’s 1964 novel, eventually lining up the shoot in summer 1970, with release delayed until the tail end of ’71.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)